By Anja Homburg, Disability Resource Centre DRC

Introduction

Frank Hall-Bentick was one of Australia’s most prolific and celebrated disability advocates and campaigners.

Frank was at the forefront of disability rights since 1981 when he co-founded the Disability Resources Centre DRC in Melbourne where they advocated for:

- accessible public transport,

- deinstitutionalisation,

- equal opportunity employment

- and much more.

He ran the organisation for many years and continued to play an active role as a non-executive director to the very end. He also established and chaired the Australian Disability and Indigenous Peoples Education Fund, whose work was close to his heart.

He was one of the country’s, and the world’s, most prolific and celebrated disability advocates. A recipient of the Order of Australia and an Australian Centenary of Federation Award, Frank was party to the drafting of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of People with Disabilities (UNCRPD), a resource person to the United Nations Bangkok, and a contributor to seventeen disability rights organisations. Frank proved that you don’t have to be showy to get things done.

He was also a well-known figure internationally, engaging deeply and tirelessly with global disability movements, particularly through his work with Disabled Peoples’ International.

Frank passed away on 24 May 2023.

Watch Video

A video of Frank talking about his disability advocacy from the DRC Leadership Series: Frank Hall-Bentick from DRC Advocacy. (1.26 mins)

Read Interview

Find out more about Frank’s life in an interview conducted by Anja Homburg in 2019 for Disability Resource Centre. Here is the full interview or download the PDF.

A Patient Man

Frank Hall-Bentick has spent almost forty years fighting for the rights of people with disabilities. As part of the Disability Resources Centre’s Leadership Series, he speaks to Anja Homburg about his life and work.

Frank Hall-Bentick is an unassuming presence. Soft spoken. Mild mannered. He tells jokes with a tone so similar to the one he uses to state facts that you’d be forgiven for thinking he was being serious. Only those who know him – who recognise the brief smile that passes over his lips and the glint in his eye – will offer a laugh, reassuring the rest of us that he really is kidding. His fierce intelligence is unmistakable, but it would still surprise many who meet him to learn he is one of the country’s, and the world’s, most prolific and celebrated disability advocates.

A recipient of the Order of Australia and an Australian Centenary of Federation Award, Frank was party to the drafting of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of People with Disabilities (UNCRPD), a resource person to the United Nations Bangkok, and a contributor to seventeen disability rights organisations.

Frank proves that you don’t have to be showy to get things done. And he continues to subdue his accolades. Despite still serving on numerous boards as well as running his own organisation, the Australian Disability and Indigenous Peoples’ Education Fund, he refers to himself as “retired”.

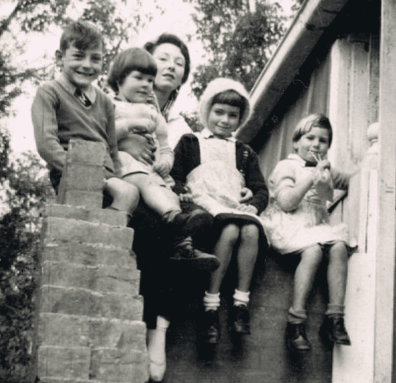

Born in Port Fairy in 1953, Frank was the second of four children. He and two sisters, Susan and Lesley, grew up with conditions that affected their spines, tissue and breathing. Eventually diagnosed as Familial Peripheral Neuropathy, the siblings’ disabilities were never fully understood. “They don’t really know what it is.” Frank says with a shrug. When I go to research Familial Peripheral Neuropathy, I see what he means. The condition, while only vaguely characterised, is adult-onset. But Frank, Sue and Lesley spent large parts of their childhood in hospital. “It was what we knew: doctor’s appointments and occasional hospital stays…. We got closer together. We were pretty much by ourselves for months (in hospital). Our younger sister Annette felt left out because she didn’t get to go to the hospital. She always envied us getting all the attention. Until she got her tonsils out. She wasn’t so keen after that.” He laughs.

But even having one’s tonsils out is a cake walk compared to the surgeries the other three Hall-Bentick children endured. In 1964 and 65, they each had metal rods inserted along their spines in an attempt to prevent them from further curving. “They didn’t really work, so they had to take them out.” Frank says. He goes to move on to another topic, but I stop him. What does he mean by “didn’t really work”? How did the doctors know they weren’t helping? He gives me a considered look – he’s not sure I really want to know. I press further and he finally comes clean – the rods began to poke out of their backs, cutting through the skin. The image sears in my mind and I look at him in horror. He barely blinks. It seems to me a gross case of medical misjudgement. Wasn’t he angry, livid even? He shrugs again. “They didn’t really know how to help us – they were just trying things out. It worked on some kids, just not on us.”

On the topic of things that didn’t work, Frank tells me another story about the evangelist faith healer Brother Ted, who visited Melbourne when Frank and his sisters were children. Family friends told Frank’s mother Brother Ted might be able to heal her three children. “She left the decision to us, and we wanted to please her by trying everything possible. We were each led to the front of the congregation and Brother Ted took us in hand, and after much violent shaking and mumbling, told the congregation that we would now be cured. Of course we hoped this would be so, but real-life showed us that there are no miracles or easy fixes to people’s lives.”

Photo: Frank, Annette, Sue and Lesley Hall-Bentick

Photo: Frank, Annette, Sue and Lesley Hall-Bentick

His eldest sister Sue died of pneumonia in 1975. His other sister and fellow disability advocate, Lesley Hall, died in 2013 of a suspected heart attack. Lesley’s passing was deeply felt throughout the disability community, most keenly by her brother, who had worked alongside her for decades.

It was Lesley who got Frank involved in disability advocacy. While she was at university Frank watched his sister become engaged in politics, feminism and direct action. Her bold, overt passion ignited his own, and the two would champion the rights of people with disabilities for the rest of their lives.

A particular focus for Frank was the deinstitutionalisation of people with disabilities, informed by his years in special education. He and his sisters attended the local primary school until mobility problems made accessing the campus too difficult. Then they were moved into schools designed for children with disabilities, run by the charity Yooralla. The consequences of the shift were largely negative. “We were segregated from our local community. We had many friends when we went to primary school. We no longer saw them. The upper part of the secondary education was done by correspondence with part time teachers assisting you. You didn’t have many peers around you that you could debate or reflect on issues with.” He tells me.

In addition to being an isolating experience, Frank’s time at Yooralla Balywn was characterised by a lack of personal freedom.

“(In Year 12) I had to go in front of a committee of about fifteen doctors, OTs and teachers to work out whether I was better for sheltered employment or I might get some help to go to university. I felt quite lucky in that they thought I could go to university.” He says with a smile in his eye, acknowledging the absurdity of needing permission from anyone to apply for further study.

But Frank didn’t qualify for university. Despite his obvious intelligence, the education he received didn’t allow him to pass his HSC. At this point the Commonwealth Rehabilitation Service contacted him about offering financial and medical support. Once again he was knocked back, this time by the CRS doctor. “(He) didn’t think I’d live very long, so didn’t recommend that I get assistance from them.” He meets my shock with a smile. “That made me a bit annoyed, as it might.”

A bit annoyed. Sure.

At moments when many of us would be paralysed by bitterness or rage, Frank Hall-Bentick decides to find another path. Refusing to do the menial, underpaid work on offer in sheltered workshops, he found work correcting tests for the Commonwealth public service. For the next nine years he worked as a public servant, focused on building a sustainable career. During this period, the Disability Resources Centre was born.

1981 was declared the International Year of Disabled Persons, and was, as Frank describes it, “a big love-in for people with disabilities”. He, Lesley and many others were concerned about the tokenism of the year, and that support for people with disabilities wouldn’t continue beyond the event’s 12-month period. Lesley partnered with VCOSS to start the DRC, an organisation they hoped would “continue the fight” for people’s rights.

At Lesley’s urging, Frank helped set up the DRC, folding letters and filling envelops. It proved to be a transformative experience. “Up until then, other than the social side of being involved with people with disabilities, I hadn’t really looked at any action…. (Through DRC) I met other people with disabilities who were also looking to change things,” he says. Inspired by the possibilities of disability activism and frustrated by a lack of advancement in the public service, in 1984 Frank became the DRC’s manager.

The slogan most often used in the early DRC years was “Nothing about us without us”, a testament to how rarely people with disabilities were asked about their own wants and needs. This simple slogan formed the foundation for Frank’s continuing effort for those with disabilities to be fully, productively and freely integrated into society.

Many people with disabilities were fed up with charities and governments making decisions for them. As Frank’s education demonstrated, the institutional models often perpetuated negative and underwhelming ideas of what community members were capable of. Many of his friends entered the sheltered workshop system when they finished schooling. “That was a very limiting experience for them… After a number of years at the sheltered workshop some of them decided it wasn’t for them. So they tried to get work outside.” He sighs “Some did, but the vast majority didn’t. So segregation and very limited outlooks on people’s abilities were very detrimental in terms of getting the best out of people and challenging them.”

Where an outdated model failed to challenge, the DRC pressed hard for change. “We challenged everything.” He says “We challenged special schools, sheltered workshops and community houses for people with disabilities. We challenged large institutions.”

Frank and the DRC demanded that people with disabilities be able to flourish and exercise the same choices as anyone else.

But the DRC was not the only place where Frank left a mark. He engaged deeply with disability movements globally, particularly Disabled Peoples’ International, travelling the world to help governments and NGOs improve their relationship with the disability community. I ask what the differences were between disability movements in Australia and elsewhere. In many places, he tells me, the old charitable and institutional models continued to dominate the landscape. “(There wasn’t) a vision that people could do more… The services were what they (the providers) thought people needed – particularly around sheltered employment.” Much like the experience of Frank and his peers, what people with disabilities envisioned for themselves was at odds with those of service providers.

They wanted everything we wanted. They wanted to have families, they wanted to a have job out in society, they wanted award wages, they wanted to go to university. It was nothing like the advisors, the old system that was working in these countries told us they wanted. They didn’t… They were never asked.

Photo: Lesley Hall and Frank Hall-Bentick

Photo: Lesley Hall and Frank Hall-Bentick

The outcomes of Frank’s work in Australia and globally were generally positive, but not everyone welcomed the new ethos. In particular, attempting to do away with the institutional model met with resistance. “That brought a lot of angst from the community, from a lot of parents who had fought for many years to get some services for their kids and here we were challenging it.”

Even today, he notes, many parents struggle to get their children accepted into mainstream schooling, making specials schools and home schooling their only options. “Mostly that’s because schools haven’t really trained teachers in how to teach diverse children and children with disabilities… The challenge in the future will be to get the resources and training for teachers to include everyone in their regular classes.”

Photo: Frank receiving the Order of Australia.

Photo: Frank receiving the Order of Australia.

This is a theme in my conversation with Frank: things are better, in large part thanks to the work of activists like him, but there is more to do, another challenge on the horizon.

This is no better demonstrated than in his work on public transport. Up until 2001, Melbourne’s tram network was completely inaccessible, with trains and buses not much better. For people with disabilities trying to enjoy an independent life, this was a huge barrier. Frank and other members of the DRC fought hard to raise awareness on the issue.

“To get a job, people needed to have accessible public transport. Nearly every year we had a forum around transport issues.” He says. They also took to the streets for direct action, chaining themselves to trams and disrupting traffic. An attention-drawing, but not always well received, tactic. “We’d block the trams for miles. People would get off the trams and some would say ‘Good on ya’. Other people would say ‘Die ya bastards!’” He laughs.

Since Frank and the DRC began campaigning for accessible transport forty years ago, things have shifted. But only from “not accessible at all” to “sort of accessible sometimes”. I ask Frank if he thinks we have the accessible tram network he spent most of his life fighting for. “Not yet, but we’re a long way closer.” He says with what I have come to realise is his signature positivity. The level of tram stops, he reminds me, continues to pose problems. “We’ve got 250 accessible stops out of 1800. We’ve still got a long way to go.”

And we do. But a reflection on the life of Frank Hall-Bentick also demonstrates how far we’ve come. How far he, and people like him, have taken us. Throughout our conversation I have marvelled at the peaceful and patient way he speaks about injustices that fill me with shock and rage. Archaic medical procedures, blatant discrimination, institutional isolation, verbal abuse. He has spent his life fighting to correct these wrongs, but they are far too familiar to shock him.

I realise my ability to be amazed by the stories he finds so commonplace is a gift. The gift of living in a world where these stories of inequality are becoming less frequent, if still all too common. The gift of being a young disabled woman who has always expected to have control in her own life. In a very real way, it is a gift given to me by this very man. By him and the many other activists who have spent decades fighting for a fairer world, undeterred by sometimes glacial progress.

What I’ve learned after many years of being involved in disability advocacy is that you need to be persistent and tenacious. It’s not a short campaign. There may be some wins that we get quickly, but most of it’s going to take people’s lifetimes.

He tells me.

And there it is. Tenacity. Patience. The willingness to devote a lifetime to making things better. Three things that make Frank Hall-Bentick a remarkable man.

Download Resource

A Patient Man by Anja Homburg (PDF)

Easy Read Version

Here is an Easy Read Guide called, The story of a disability advocate called Frank Hall-Bentick, based on the above resource, Disability Advocates and Campaigners in Australia: Frank Hall-Bentick.

- Click to open PDF: The story of a disability advocate called Frank Hall-Bentick

- Click to open Word version (no pictures): The story of a disability advocate called Frank Hall-Bentick

Easy Read uses clear, everyday language matched with images to make sure everyone understands. – Council for Intellectual Disability

Easy Read documents are helpful for:

- people with disability

- people with English as a second language

- people with lower literacy levels

- people who want to learn about a topic quickly

Explore Further

- Frank Hall-Bentick AM’s website

- DRC Advocacy website

- The History of Campaigns in Australia by People With Disability

- Making Advocacy Accessible Collection in Commons Library

- Watch more videos with Frank:

Topics: Collection: Tags:

- Activists - Stories_Accounts about/by Individuals

- Frank Hall-Bentick (1953 - 2023)

- Interviews

- Movements_Campaigns - People with disability_Disabled People

- People with disability_Disabled People